I’ve spent a lot of time thinking and writing about navigating emotions and growing flexible mindsets, especially when it comes to decision-making. Now, I want to dig into something else that shapes the way we approach choices: regret and its close cousin, entitlement.

A lot of the fear and anxiety around making the “wrong” decision comes from the fear of regret. And speaking of regret, I can instantly recall that cold, sinking sensation in the pit of my stomach. It’s super unpleasant, and I’d definitely prefer to avoid it if I could.

If we zoom out and think about it with a clearer head, what is regret really? More often than not, it’s just hindsight mixed with nostalgia and self-recrimination. It’s the belief that if we had chosen differently, we’d be living in some better, more optimized version of our lives.

But that assumes there is a single “best and correct” path waiting for us. That as long as we make the right choices, we both deserve to and have the control to reach that uniquely optimal state of being. But deserving, achieving, and controlling an outcome are entirely different things. What they do have in common, though, is a sense of entitlement.

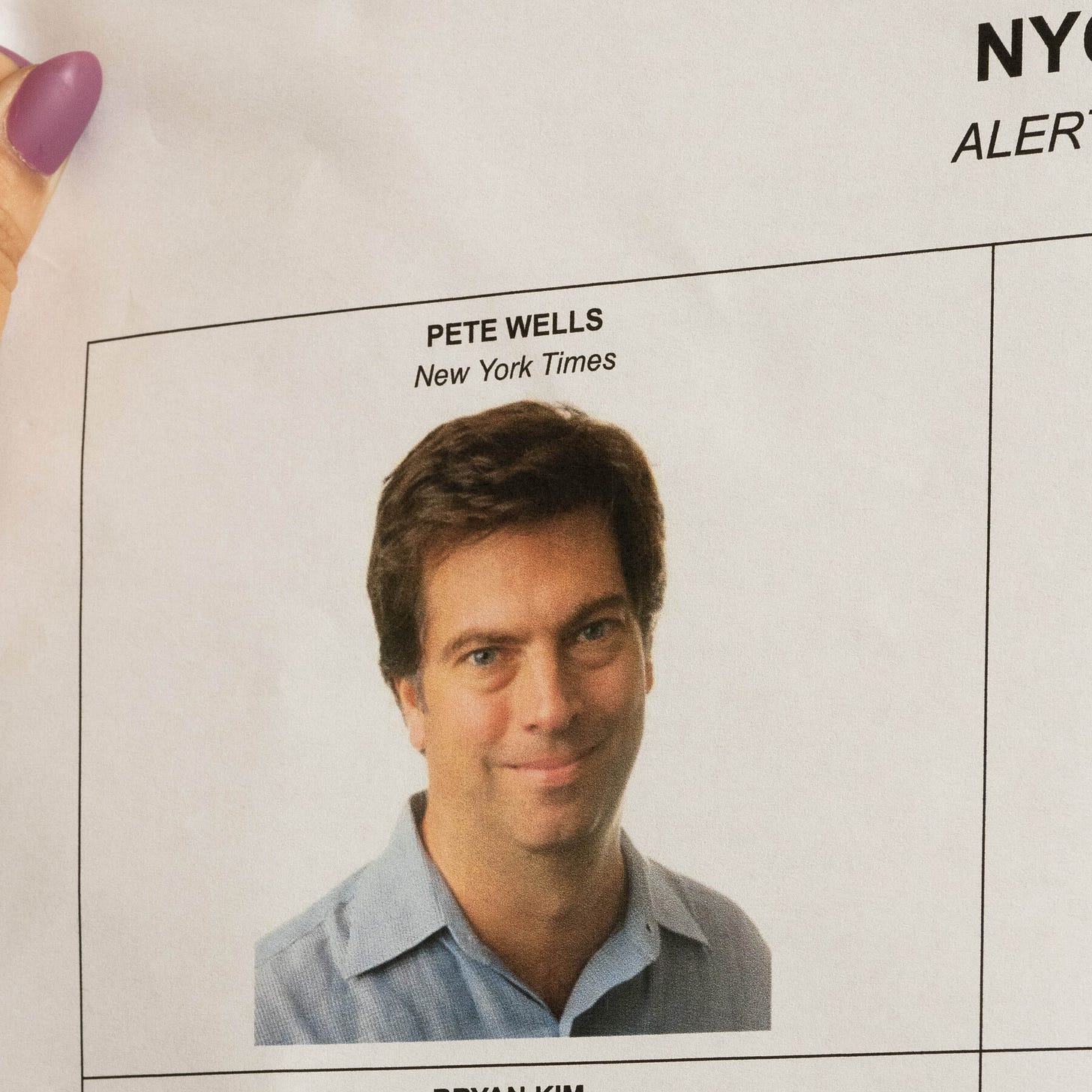

Regret feels bigger when we believe we’re entitled to a certain outcome. Take something as small as ordering at a restaurant. I’ve caught myself hoping I won’t regret my entrée choice, as if picking the “wrong” dish is some meaningful loss. That assumes I’m entitled to the absolute tastiest thing on the menu, whatever that may be.

But am I really? Just because I’m paying for a meal, does that mean I deserve the most delicious option available? From a strictly capitalistic sense, sure, I’m exchanging money for value. But is that the healthiest way to think about it? Is it the best mindset for actually enjoying the meal or for being happy in general?

Even if I were a food critic, I wouldn’t deserve to only eat the best dishes. In fact, I might actually deserve a full range of experiences, good and bad, rather than being misled by only the good, to get the most accurate representation of the restaurant.

But I digress. I’m not a critic, and my goal isn’t always to optimize for the best dish. Sometimes I do, like when I’m chasing a particular culinary experience. Other times, when I’m celebrating with friends, the food is secondary to the people I’m with.

Even so, I still get that lingering fear of ordering the wrong dish, no matter the situation. Maybe a better approach is accepting that I’m paying, both in money and time, just to get out of the house, full stop. Lol.

To really drive the point home, I often go through the same when choosing a book. I’ll pick Book A over Book B, then two hours in, start wondering if I should have chosen differently. It’s the same anxiety of over-optimizing time and minimizing regret, as if losing two hours could somehow throw my entire life off course.

And even if Book A is objectively worse than Book B, regretting those two hours won’t change anything. It might still come in handy later—maybe in a conversation where Book A comes up and I can say with certainty that I couldn’t stomach finishing it. That might lead to an interesting discussion or a book recommendation I wouldn’t have found otherwise. So those two hours reading crap isn’t necessarily wasted. It’s just repurposed in ways I couldn’t have predicted when I first made the choice.

Entitlement gets even trickier with bigger life decisions. At its core, entitlement is the belief that effort guarantees reward. That if I work hard and invest the time and energy, I should get the outcome I want.

But as we all know, life doesn’t work that way. You can put in years of effort and still miss the promotion. You can plan the perfect vacation only to cancel it for a family emergency. You can quit smoking today and still be diagnosed with cancer five years later. (But that doesn’t mean quitting was the wrong choice. It might have been the difference between five years instead of one.)

Regret thrives on entitlement. It convinces us that if we had just chosen better, we would have gotten the outcome we deserved. But deserved according to whom? No single decision holds that much power, even if it feels like it does in the moment. Most of what seems like a big deal today won’t even matter a year from now.

Instead of treating regret like something to fear, it’s worth asking instead:

Will this matter to me in a year? In five?

If so, is this something I can never walk back from?

Is lifelong unhappiness really the worst-case scenario? Does lifelong happiness or unhappiness even exist?

The reality is, very few decisions are truly irreversible. Dishes can be sent back, careers shift, relationships evolve, and failures turn into insights and stories.

Most “suboptimal” choices are just detours. The only truly irreversible ones are the extreme ones, like murder. So don’t do that.

No one is entitled to all the best insights, hidden secrets, or every “right” choice. We’d all love to have them, but that’s neither realistic nor possible. The best way forward, at least as I see it right now, is to keep making choices, commit to them, deal with the consequences, and learn what you can.

There will always be a next decision. With that in mind, I’m focusing less on avoiding regret and more on changing my relationship with it. I know I can’t avoid feeling regret entirely, so when I do feel it, I’m trying to see it as proof that I’m making choices and taking risks.

Regret doesn’t have to be a punishment, but that doesn’t mean I’ll ever like dealing with it. Still, I’d rather face its sting than let it make my choices for me.